Currently reading

I enjoyed this book immensely. It's about a lot more than the value of checklists, though it is absolutely about that. It's a practical treatise, though, on recognizing our own limitations and fallibilities. Even (or especially) if we are highly trained, specialized professionals. It has a lot to say about skepticism as the foundation of science, and how difficult it can be to remember that. Gawande relates the challenges he's faced in getting medical professionals to accept the benefits of this practice, even in the face of research--there is such a tendency to cling to intuition and gut reaction, even in the face of growing evidence that questions it.

2

2

An interesting book, though perhaps not as compelling as it might have been. Winchester seems to vacillate a bit between wanting to write a technical book on the geothermal workings of the planet and wanting instead to write a narrative history populated by individual people who witnessed or were affected by the quake. When he takes an extended trip to either end of the spectrum, the book is more interesting than when he carefully treads down the center. It's a worthwhile read, don't get me wrong. But I wish he had written a longer book that encompassed more of both. The narrative history, especially, would have benefited from really following the individual characters he introduces.

2

2

You don't have to know me very long to know that I'm a huge fan of Elizabeth Warren. What I'm not a fan of, though, is political memoirs. They tend to be didactic in the worst way, shallow, and transparently self-serving. It's unusual that I'll even give one a look, and very rare for me to finish it. But I enjoyed this one quite a bit. Warren is, I suppose, doing the things such a memoir is supposed to do—laying out her case for the causes she's identified with, making herself seem fully human to people who will never meet her, etc. But she does them quite effectively. Obviously this book probably isn't going to change your mind if you're fully opposed to her political & economic views (though there's always hope, I guess). But it does lay out those views in a way that is both accessible and fully accurate. And it's hard not to empathize with her as a novice politician, describing the personal and public challenges she faced on this career path. When I started the book, I doubted I'd finish, and truly doubted it would make me any more enamored with her. I was wrong on both counts.

2

2

I am not sure how much I trust Fleming as a historian; she often seems to soften her assessment of the Romanovs' actions and beliefs, and her descriptions of Lenin seem deliberately snide. Not that she is, strictly, inaccurate in either case, but her writing does seem to have a slant. Still, for me it was a pretty good introduction to this period in Russian history. I knew the general sketch of what had happened, of course, but Fleming does a good job laying out the details—even when they are pretty complex, and might easily be convoluted in a lesser writer's hands. From a narrative standpoint, she chooses well which parts to devote close attention to and which to paint in broad strokes. What might have been either dry or overly romanticized ends up being neither.

3

3

Not quite as strong as the previous two, especially the first. The exposition is a bit blunt here, as Pullman tries to cover a lot of mythological ground in a relatively short space. It's certainly an adequate finale to the series, though.

Really thought-provoking work. Sagan's even-handed, open-minded approach to all streams of thought is refreshing and thoroughly engaging. He writes with a truly infectious sense of the beauty inherent in a cogent, thoughtful worldview. I won't bother speaking in a lot of detail about the book, but I will highly recommend it.

Sheds a lot of light on its chosen historical period, and there's a lot there to see. The journalism taking place, especially, was truly fascinating. In fact my biggest complaint with the book might be that she sort of drops the journalism thread following the McClure's shake-up. She does touch base with those characters sporadically throughout the rest of the book, but not with the care and diligence that she employed before. In a sense it's a shame that Goodwin is a presidential historian, because I would have loved for this book to be centered on Ida Tarbell herself.

In any case, it's a beautifully written book; always compelling and informative, as I've come to expect from the author. I have a richer understanding of American history for it, and certainly a clearer understanding of Roosevelt & Taft. Highly recommended

I wish the rest of the book had as much to say as the epilogue, not to mention that it had said it with as much passion. I didn't put the book down, so I guess I'd say it was worth reading. But I can't really recommend it, unless you really do just want a follow-up on Amazing Grace.For the children of a ghettoized community, the pre-existing context created by the social order cannot be lightly written off by cheap and facile language about ‘parental failings’ or by the rhetoric of ‘personal responsibility,’ which is the last resort of scoundrels in the civic and political arena who will, it seems, go to any length to exculpate America for its sins against our poorest people.

Sheds a lot of light on its chosen historical period, and there's a lot there to see. The journalism taking place, especially, was truly fascinating. In fact my biggest complaint with the book might be that she sort of drops the journalism thread following the McClure's shake-up. She does touch base with those characters sporadically throughout the rest of the book, but not with the care and diligence that she employed before. In a sense it's a shame that Goodwin is a presidential historian, because I would have loved for this book to be centered on Ida Tarbell herself.

In any case, it's a beautifully written book; always compelling and informative, as I've come to expect from the author. I have a richer understanding of American history for it, and certainly a clearer understanding of Roosevelt & Taft. Highly recommended.

An interesting—and unusual—approach to history. It works well, really. I didn't entirely trust the history presented; it seemed a bit too . . . pro-establishment, I guess. Sometimes in ways that look naive with hindsight. But I did trust it enough to continue with it, and it was fun to go along with the ride. You'd have to be a bit of a history junkie to even consider a volume this size, and if you are one, you may find that it's not as serious as you'd like. But myself, I thought it struck a decent balance.

The concept of this book is ambitious, and intriguing. There are both advantages and disadvantages of this narrow approach to telling black America's history—what it lacks in breadth, it makes up for in depth. And vice-versa, it must be said. The conditions of slavery described here seem—to my imperfect understanding—to be a sort of median among the range of conditions that existed. But having some sense of the extremes makes for a much fuller understanding. That said, of course, it can hardly be the job of one single book to create that fuller understanding. And the depth of experience described here is really valuable.

I loved the book, and highly recommend it. But since I don't have much to say about that which hasn't already been said before, let me point out two things I wasn't wild about. The first is the technique Haley used to try and locate the narrative in time for his readers. Slave conversations full of names, locations, and other specific details did the expository work he wanted them to do, I suppose, but they were jarringly unrealistic. Especially in a book with so much rich detail, they really took me out of the narrative. I would much rather he simply named the years at the beginning of each chapter, or something along those lines. His characters could then have made vague allusions to events (as they surely would have in real life), rather than speaking about them as though they were teaching a survey course.

The second issue I have is more significant. Haley deals with the most recent generation or two in about as much space as it takes him to describe individual days and nights earlier in the book. It's not hard to imagine why he might do this. He may have just been ready to move on. Perhaps he thought his reader would be familiar enough with recent history so that his description wouldn't add much, and perhaps he thought recent history was simply less important than previous generations. Surely he also felt some (economic, professional, literary) pressure to get the thing done and to keep the length manageable. I have to wonder whether there was ever a discussion of making it a two-volume work, to allow more space for this part of the story, but I doubt it was seriously considered. I'm conscious of this lack, though, and it feels like a real one, partly because of Isabel Wilkerson's The Warmth of Other Suns. She points out quite well, I think, the way this chapter of America's race history has been underestimated and undervalued. She also shows quite well how individual stories can be used to illuminate it. It's a shame, really, that Haley didn't do the same.

But again, I really liked this book, those two complaints notwithstanding. I'm also aware of the controversy surrounding Haley's claims about how factual the book is. I'm put off by that, certainly. But I never assumed the book was at all factual until I finally reached the end (where he makes that claim). So I'm judging it here on its merits as a work of historical fiction, and on that ground I think it stands pretty firmly.

A simple story, beautifully told. The first 2/3 has kind of a mythical tone to it; she brings to ground gracefully, and the last act follows through nicely.

I am baffled by the people criticizing it as something only adults can enjoy. It came to me by recommendations from my son and daughter. It's intriguing enough to keep an adult engaged, certainly, but neither of my kids had any problem engaging with it themselves. I highly recommend reading this with, or alongside, your kids.

My daughter read this book and loved it so much that she's gone on to read every other Sharon Creech book. I thought I'd give it a look, if only as a conversation piece, and I'm so glad I did. Not only did I love the book, but I'm so glad that such a talented writer has dedicated herself to kids' books—what a treasure!

I vacillated as I read this. I was often engrossed in Thoreau's twin urges—to simplicity, and to presence in each moment within nature. But I was repelled by his twin delusions—that the poorer a person is, the happier he must be, and that Thoreau himself was aware of the One True Way to live. He spends an awful lot of time disparaging the common actions & manners of virtually every human being other than himself. And over & over again he valorizes poverty, in a way that makes one doubt he's ever actually experienced it.

But after all, those are mostly just faults in the author's voice, and they're more than outweighed by the moments of clarity and presence that suffuse the book. I remembered a lot of the quotes, of course—"In wildness is the preservation of the world", "If you have built castles in the air...", "If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer", etc.—but to come across them again in context was to encounter them as new. There's a richness and texture to Thoreau's philosophy that's really quite gorgeous. I was glad to spend time there.

In some ways, less compelling than the first of the series. The mythology of the first one, I guess, was more interesting to me. I also liked the side characters from the first better—Iorek Byrnison, John Faa, Farder Coram—and the cultures they represented.

That said, this book was still a good one. The action & pacing were steady, and the suspense perhaps even increased. I'm ready for the next, to finish the series.

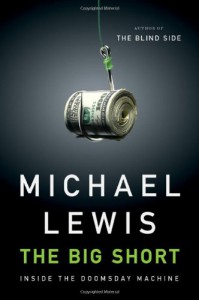

A fascinating read. Michael Lewis has a well-deserved reputation for taking dry, complex subjects and making them accessible and interesting. He earns it pretty well here. There are still a lot of things I don't understand about the financial markets in which this book is set, but I got what I needed to enjoy this book. His biggest trick, of course, is simply personalizing the issue. It doesn't have to be about what it's about; it can be about the people involved. Which is pretty much what carries this book. But he's done a good job choosing his characters, and a great job bringing them to life.

I probably should have read Liar's Poker as an introduction to his work, and maybe I'll do that one next. But I enjoyed this one quite a bit.

1

1